Modern Philosophy

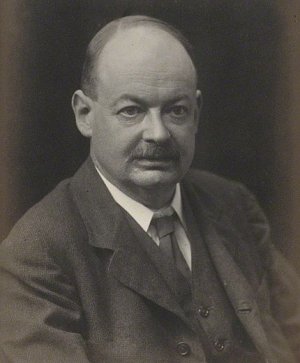

In the 20th Century, the philosophical debate on the nature of time continued unabated, given new impetus by the work of the British idealist philosopher J.M.E. McTaggart, particularly his 1908 paper, The Unreality of Time.

McTaggart argued that time is actually unreal because our descriptions of it are necessarily either contradictory, circular or insufficient. McTaggart pointed out that we see the present moment we are living through as the ONLY present time. But, all other moments, past and future, also either were or will be the present time at some point or other, so how can this contradiction be reconciled? McTaggart’s detailed analysis subsequently led to a number of productive areas in the modern philosophy of time, including the tensed and tenseless theories of the passage of time.

Tenseless and Tensed Theories of Time

The tenseless theory of time (also known as the B-theory, based on McTaggart’s B-series method of ordering events) calls for the elimination of all talk of past, present and future in favour of a tenseless ordering of events using only phrases like “earlier than” or “later than”. The argument behind this is that tensed terminology can be adequately replaced with tenseless terminology, e.g. the future-tensed sentence, “we will win the game” can be adequately expressed as, “we do win the game at time t, where time t happens after the time of this utterance”. The future tense has therefore been removed, and the verb phrases “do win” and “happens after” are logically tenseless, even if they are grammatically in the present tense. If this is true, then there is no essential difference between the past, present, and future, all of which are therefore equally real (see the section on Eternalism below), and the passage of time must be merely an illusion of human consciousness.

The tensed theory of time (the A-theory), on the other hand, denies that such an argument is valid, and argues that our language has tensed verbs for a good reason, because the past, present and future are very different in quality. The A-theory therefore denies that the past, present and future are equally real, and maintains that the future is not fixed and determinate like the past. A-theorists believe that our ordinary everyday impression of the world as tensed reflects the world as it really is: the passage of time is an objective fact.

Presentism and Eternalism

The philosophy of time that takes the view that only the present is real is called presentism, while the view that all points in time are equally “real” is referred to as eternalism.

Thus, according to presentism, only present objects and present experiences can be said to truly exist, and things come into existence and then drop out of existence. Therefore, past events or entities, like the Battle of Waterloo or Alexander the Great, literally do not exist for presentists, and, because the future is indeterminate or merely potential, it cannot be said to exist either.

Eternalism, on the other hand, holds that such past events DO exist, even if we cannot immediately experience them, and that future events that we have not yet experienced also exist in a very real way. For eternalists, the “flow of time” we experience is therefore just an illusion of consciousness, because in reality time always everywhere. Eternalism takes inspiration to some extent from the way time is modeled as a fourth dimension in the theory of relativity of modern physics (see the section on Relativistic Time), so that future events are “already there” but just have not been encountered yet, and the past literally still exists “back there” in the same way as a city still exists after we drive away from it. This is often referred to as the block universe theory or view because it describes space-time as an unchanging four-dimensional “block”, rather than three-dimensional space modulated by the passage of time.

There is also a variation of eternalism, sometimes known as the growing block universe theory of time or the growing block view, in which more and more of the world comes into being with the passage of time (hence, the block universe is said to be growing), so that the past and present clearly do exist, but the future is not yet part of this universe and therefore does not exist. This in some ways gels with our intuitive impression that the past (which is fixed, and can be accessed through remembering and physical records) is very different in nature from the future (which is variable, uncertain and cannot be accessed or consulted).

Endurantism and Perdurantism

A similar but separate dichotomy exists with regard to the persistence of objects through time. Endurantism is the more mainstream or conventional view, asserting that, when an object continues to exist through time, it exists completely at different times, with each instance of its existence fundamentally separate from the other previous and future instances. Perdurantism, on the other hand, holds that something that continues to exist through time exists as a single continuous reality, and the thing as a whole is then the sum of all of its “temporal parts” or instances of existing (the temporal parts of a particular person, for example, include their childhood, middle age, old age, etc).

This argument goes back to ancient Greece and Heraclitus’ contention that we can never step into the same river twice (because the water is not the same water the second time around). An endurantist would tend to agree with Heraclitus, even though our common sense tells us that the river at one time and the river at another time are in fact the same river, and nothing about it has essentially changed. A perdurantist, on the other hand, would argue that it is possible to step into the same river twice by stepping into two different temporal parts of it.

Typically, presentists are also endurantists, and eternalists are perdurantists, although this is not necessarily the case.

New Philosophical Ideas from Modern Physics

The concept of alternative universes and the many-worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics (see the section on Quantum Time), which is gaining increasing attention in the world of modern physics, adds a whole new dimension to the discussion of the nature of time. In the disconnected time streams in a potentially infinite number of parallel universes, some could be linear and others circular; time could continuously branch and bifurcate, or different time streams could even merge and fuse into one; the laws of causality and succession could break down or just not apply; etc, etc.

Although modern physicists generally believe that time is just as “real” as space (see the section on the Physics of Time), a few mavericks, such as Julian Barbour, have tried to show scientifically that time exists merely as an illusion. In his 1999 book The End of Time, Barbour makes the argument that the quantum equations of the universe only take their true form when expressed in a timeless realm that contains every possible “now” or momentary configuration of the universe, a realm Barbour called “platonia”. Barbour argues that, in order to reconcile general relativity with quantum mechanics, either time does not exist, or else it is not fundamental in nature.

The possibility that time might have more than one dimension has occasionally been discussed both in physics and in modern analytic philosophy. The English philosopher and scientist John G. Bennett has posited a six-dimensional universe, with the usual three spatial dimensions and three time-like dimensions, which he called time (the sequential chronological time that we are familiar with), eternity (cosmological time or timeless time), and hyparxis (characterized by Bennett as an “ableness-to-be”, and may be more noticeable in the realm of quantum processes).

Imaginary time is a concept derived from quantum mechanics. Stephen Hawking introduced the concept in his 1988 book A Brief History of Time as a way of avoiding the idea of a singularity at the beginning of the universe, where time suddenly starts and all the laws of physics break down. Hawking proposed that space and imaginary time together are finite in extent but with no boundary (in a similar way as the two-dimensional surface of a sphere has no boundary). Imaginary time is not imaginary in the sense that it is unreal or made-up, but it is admittedly rather difficult to visualize. It is perhaps easiest to think of as a line perpendicular to the past-future line of regular or “real” time, in much the same way as the imaginary numbers run perpendicular to the real numbers in the complex plane in mathematics. Under this model, “real time” as we know it would still have a beginning, but the way the universe started out at the Big Bang would essentially be determined by its state in imaginary time. The beginning of the universe would then be a single point, analogous to the North Pole of the Earth, but not a singularity.